or: The Road to Hell is Paved with Good Intensions

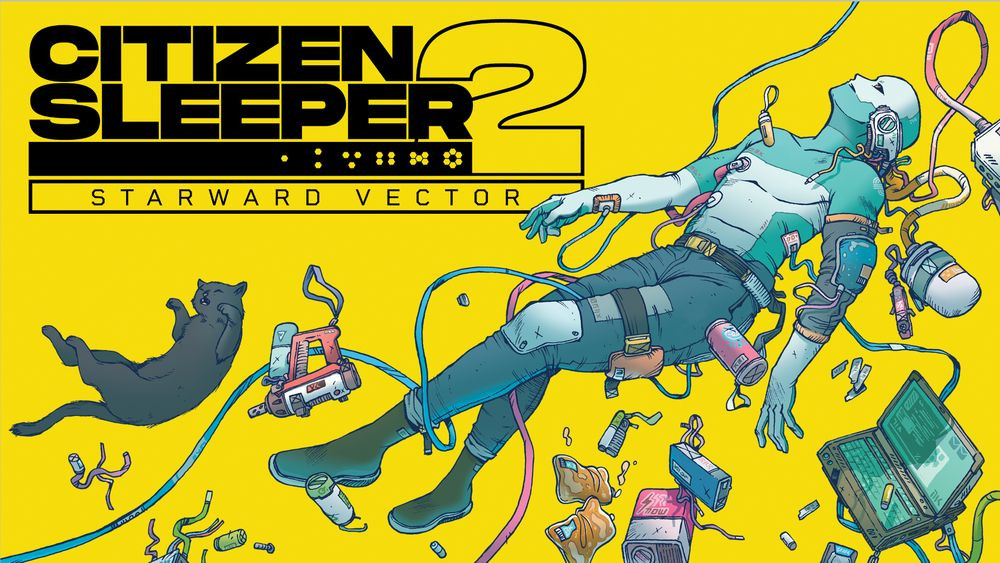

Citizen Sleeper 2: Starward Vector (reviewed)

That we each have our own opinions and definitions of what is and what is not art is not a controversial point. The arguments for what constitutes ‘art’, much like those of obscenity, reductively land on “I know it when I see it”. Art must be created in a medium, even if that medium is the movement of a body through position and time, but it is similarly uncontroversial to suggest that not all movies, novels, paintings, or any other utterance by human can automatically be considered art. Art is subjective; one person’s masterpiece is another person’s counter-point to what does and does not define ‘art’. The more one is invested in a medium, the more likely they are to have an opinion as to whether or not works within that medium can be considered art, and the more strongly held that opinion is likely to be.

Roger Ebert, a man who made film criticism into art, were it not already consider so, is one of many voices chime into the ‘video games aren’t art’ debate; Hideo Kojima is another. In both cases they argue that the level of control the player has in shaping the narrative means, unlike any other text, a video game cannot be art. Ebert would have it that if the player was able to prevent Juliet from yielding her “happy dagger”, then the point of the English-speaking world’s most famously doomed lovers would be lost. Sadly for us, perhaps less so for him, he did not have push through The Last Of Us: Part II’s gruelling ending, a sequence in which I would have gladly relinquished my weapon, and did relinquish my controller, many times, in the forlorn hope doing so would invoke a different ending. It did not.

Any piece work by a human that connects the reader, viewer, player with another human has an artistic quality. Art is created when a universal human language is deployed, and is skilfully, artfully (that being original meaning of the word), crafted in a way that resonates with another person. Within their medium, Citizen Sleeper and its sequel, Starward Vector, are art. A one-person development team has created an experience that encapsulates their own, as a non-binary person at the fringes of late-stage capitalism and the gig economy, and distilled some of that into a game that is at once hard science-fiction and entirely human. As an android body with an uploaded human consciousness, fighting for its freedom from the kind of corporation that would take a human consciousness as repayment for debt and use it for slave labour, Jump Over the Edge developer Gareth Damien Martin creates a world of hard edges, difficult choices, and limited resources to help or hinder your escape. In the original game, your Sleeper, the android body and its digitised human consciousness, has fled from servitude to dilapidated space station The Eye. Through one story line in the original, the effect of the game was such I had to sit with an ending I had chosen and come to terms with the decisions I had made that got me to that point, not in the game, but at that point in my life. By shaping the action, the ending had a much more profound effect on me than that of centuries-dead doomed lovers, but I do Shakespeare an injustice: R&J is not The Bard’s best.

For a 12 – 15 hour game, Citizen Sleeper is a difficult one to follow, and the approach not to follow it directly is a wise one. Starward Vector finds us inhabiting the body of a different Sleeper, though one we have chosen from the same three classes as available in the previous game. Our time to the enslaving corporation served, we find ourselves working for ambitious gangster Laine, who we like no more than our previous ‘employer’. Presumably: it’s hard to know for sure, because to escape him, we’ve had to reboot our body, aided by fellow escapee Serafin. The reboot has failed, interrupted in startup, wiping our memories. We don’t remember Serafin, much as we try, but we quickly come to learn that Laine is a threat, one that will follow us and hunt us as we escape in our commandeered ship, The Rig. Unlike our Sleeper in the original game, we are freed of the need for Stabiliser, a limited resource that drove decisions, increased risk, and limited actions. Now the driving mechanic is Stress, with the additional challenge of dice that will break and glitch. Combined with the age-old “powerful need to eat” that haunts life across the ‘Verse, Stress will cause your dice to break and that and hunger/a lack of energy will affect the number of dice you have. Replacing the need for Stabiliser with Stress changes the way the game is played, bringing a level of personal involvement to the missions and side-quests. Stress affects not only your own performance, but that of the shipmates you choose to help out on Contracts, side quests picked up from interactions along the main story. Choosing a low-rolled die to facilitate a task can easily result in failure, a knock to your shipmates’ confidence, and, when battered enough, to them dropping out of the mission. Leaving our Sleeper to overstay their time in side-quests and break their remaining dice, such is the idiot need to “help” by setting ourselves on fire to keep ungrateful traders warm.

In the later stages of the game, the mechanics become more visible. Having attacked the plot entirely out of sequence, we have permanently glitching three of our dice. With only three roles left, and all of those populated by glitched dice that have only a 20% chance of success, that 1-in-5 success will sometimes appear more frequently than the odds would have it, particularly when it suits the story to do so. This observation may, in and of itself, be nothing more than chance, but there’s a degree of necessity to this. It’s the dice-based system is butting up against the narrative drive. Strictly speaking it should take roughly five times longer to get through the missed story section, playing now with fewer dice and most of those glitched, but necessary sections of plot seemingly attract more positive outcomes from the impossible geometry of a five-sided die. While there’s relief for the multiple against-the-odds positive outcomes, without which the game would be near-unplayably frustrating, it does highlight the shortcomings of the mechanic that drives the game, and which serves as part its emotional core: with competing clocks, one counting successful rolls, the other measuring failed rolls or else some other limiting factor, there are quests requiring such a number of successes that the odds are, literally, stacked against us. Not that this will stop a determined player. The quality of Damien Martin’s writing, the future brought to life as much by the scale of the Helion system the story plays out in as the dents and knocks to our Sleeper’s body and to The Rig we escape in, and such are the plights and stories and richness of the characters and denizens of this expansive world, that we linger in side quests, wasting resources and chance, in the forlorn hope our good intensions will ‘help’. Even in the face of astronomical odds of those dice and clocks, the richness of the location and the detail and the people, make us want to stay—to do otherwise is to abandon a person. So we stay, trying to make some slight improvement to a fleeting person’s troubled life, our Stress levels pushed to extreme, our supplies run low and then run out, that our Sleeper’s body forced to shutdown and reboot, causing permanent glitches to our dice.

The dice mechanic is the game. Without the element, or even the illusion of chance, of risk, there is no peril, the game would not resonate so emotionally; our Sleeper is being broken by our actions and choices and the resulting Stress, so the greater our connection to them, the stronger our empathy, the more we are moved by their plight, and the plight of those around us. The dice mechanic, flawed though it may be, gives a physical measure of the actual cost of our actions, a means to calculate the risk to our plans, and measure the safety of ourselves, and our burgeon crew of waifs and strays picked up en route, from co-captain Serafin, to a motley crew and a stowaway.

Citizen Sleeper2: Starward Vector stands out as a game because of the quality of the writing, and the characters it conjures, combined with the mechanics of chance, however orchestrated, that make for an experience that is connecting and human. The world of Citizen Sleeper could exist in any medium, and absolutely should, so rich is the vein for mining. But the experience of Starward Vector, like that of the original game, is one that can only happen in the medium of games, and specifically video games in this particular example. Citizen Sleeper stands out because the events that play out across the stages created by and the parameters set by Damien Martin as developer, are shaped by our actions as player characters. In its chosen medium, it is no less than a work of art.

Header image: Fellow Traveler / Jump Over the Edge